Understand And Implement Http

HTTP - intro

Buckle up, we’re gonna dive into HTTP, the protocol that powers the internet. I’m not going to start with “HTTP stands for hyper tex..”, we all learnt that as kids. As developers, we can understand it in a much simpler and relatable way.

What’s a protocol anyway?

Certain terms tend to intimidate folks, especially as junior engineers, and protocol is definitely one of them. Once you realize that all software is written by developers like you and me, things do get easier. So what is a protocol then?

Like the english word, a protocol is nothing but a set of rules that are agreed upon and followed by everyone. And network protocols can be simply be thought of as PAYLOAD FORMATS, that’s it. Seriously, your openapi spec could be called a protocol if enough people use it! 😄 (S3, openai are a few examples…)

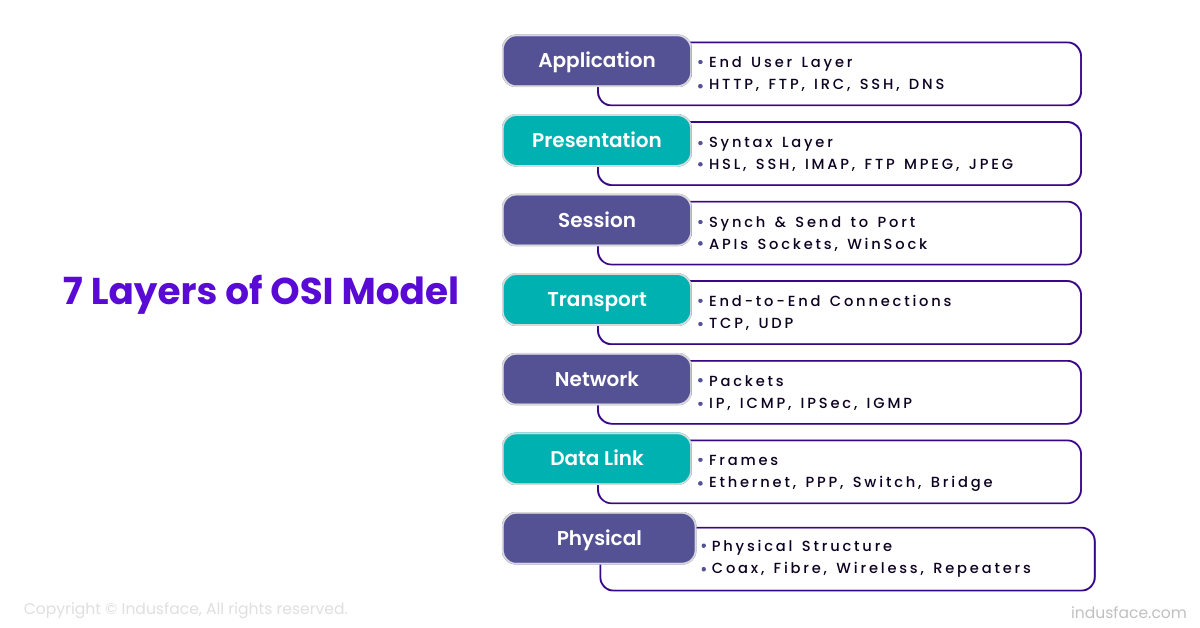

So what’s so special about HTTP then? It’s an application layer text based protocol that’s designed for exchanging text and bytes over TCP. Let’s get a quick refresher on the OSI model

OSI model

If you come from CS, you’ve seen this diagram a thousand times already. But here we go again… If you’re new to OSI, don’t worry, we’ll cover all you need to know right here

Found this really nice diagram that actually has really nice one liners with simple examples.

Here’s what we need to know..

Layer 4

The transport layer keeps track of the end to end connections and does things like handshakes, acknowledgements and package redeliveries. Bottom line, it makes sure a packet that’s sent reaches the other side.

TCP and UDP are the two main protocols here, HTTP/1.1 the one we’re buildig here is built on top of TCP. The UDP protocol is meant for cases where a few packet drops wouldn’t affect the user experience, say video streaming for example. Though nowadays our network infrastructure and error correction techniques have gotten so good, the web is eventually said to phase out TCP in favour of UDP(quic)… that’s HTTP/3.

Anyway, as far as we are concerned, TCP lets us create servers that listen on a port, that clients can connect and send data over. Here’s a quick demo using nc and telnet

1

2

3

(base) ~ ❯ nc -l -k 3000 ⏎

client sent message

server sent message

We started a server at port 3000

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

base) ~ ❯ telnet localhost 3000 ⏎

Trying ::1...

telnet: connect to address ::1: Connection refused

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to localhost.

Escape character is '^]'.

client sent message

server sent message

Telnet lets us connect to this server and send some bytes. Then, we sent some data from the server back to the client

That’s TCP. It’s pretty straightforward to implement this in most languages

Layer 7

The application layer is basically the end user logic that deals with the data to serve business logic, essentially.

Imagine a person sitting in front of a server looking at messages clients sent over TCP and replying, here’s a chatgpt illustration

What this guy is doing is the application layer. But it’s not realistic to code this way, if clients were sending whatever they want. That’s where HTTP comes in.

It defines a simple text format that’s agreed upon, here’s the RFC for HTTP/1.1, so that we can have abstractions built on top of this that we can work with across languages. Libraries and frameworks to further abstract commonly used features, to make us more productive and less error prone to build apis or web services. The level of abstraction you want to have is a discussion for another day 😄

Let’s take a look at HTTP in action like we did for TCP

HTTP at it’s simplest

Here, I’m starting a TCP server at port 3000

Now, let’s send a simple POST request with cURL that just sends an 8 byte string “hey jane”, of type text/plain

On the server side I’m literally typing out the text format HTTP protocol, which curl then understands this and parses our headers and body accordingly.

Time to code it up

Structure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

lazy_static = "1.5.0"

config = "0.15.6"

serde = { version = "1.0.217", features = ["derive"] }

serde_json = "1.0.136"

clap = { version = "4.5.26", features = ["derive"] }

tracing = "0.1.40"

tracing-opentelemetry = "0.27.0"

tracing-subscriber = { version = "0.3", features = ["env-filter"] }

opentelemetry = "0.26.0"

opentelemetry-otlp = { version = "0.26.0", features = ["default", "tracing"] }

opentelemetry_sdk = { version = "0.26.0", features = ["rt-tokio"] }

tracing-test = "0.2.5"

tokio = { version = "1.43.0", features = ["full"] }

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── config.env

└── src

├── cmd

│ └── mod.rs

├── conf.rs

├── main.rs

├── pkg

│ ├── handler.rs

│ ├── mod.rs

│ ├── request

│ │ ├── mod.rs

│ │ └── parser.rs

│ ├── response

│ │ ├── builder.rs

│ │ └── mod.rs

│ └── server

│ ├── listen.rs

│ ├── mod.rs

│ └── router.rs

└── prelude.rs

7 directories, 16 files

TCP Server

First and foremost, we need a TCP server that can read and write raw byte streams from our clients. Let’s start by defining our server struct

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

pub struct HTTPServer {

pub addr: String,

}

impl HTTPServer {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let addr = format!("0.0.0.0:{}", &settings.listen_port);

Self { addr }

}

}

the settings object here, is read from envs. Look at my rust structure blog post for more details

Now, for the actual listener… Start by initiating a TcpListener from tokio::net

1

let ln = TcpListener::bind(&self.addr).await?;

Now we need to start a listener loop that accepts socket streams from new clients, and spawns a dedicated thread for handling each connection

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

loop {

let (socket, _) = ln.accept().await?;

tokio::spawn(async move {

if handle_connection(socket).await.is_err() {

tracing::error!("error handling connection");

};

});

}

Let’s define this function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pub async fn handle_connection(mut socket: TcpStream, routes: Router<Handler>) -> Result<()> {

let mut buf = vec![0; 1024];

loop {

let n = socket.read(&mut buf).await?;

if n == 0 {

return Ok(());

}

let body = buf[..n].to_vec();

tracing::info!("body: {:?}", &body);

let res = serde_json::to_vec(&json!({"msg": "success"}))?;

socket.write_all(&res).await?

}

}

Here we’re creating a buffer of &[u8] to store our stream data, if it’s length is 0, it means the client has closed the connection, and we can end the loop.

Or else, we read the buffer up to te length from socket.read, to get our data, which we then convert to a vector, Vec<u8>.

note: many tutorials out there, will have you convert to string at this point, do not do that, cuz our requests could contain binary data as well, and HTTP… contrary to it’s name is a binary protocol

For now, let’s just print this body and return a dummy success response as shown

Request Parser

Now, in order to make it feasible to work with these requests, we build a request object that’ll be passed to our handlers, much like many micro-frameworks out there, say fastapi or axum. Axum does have a superior abstraction with it’s extractors, but that’s beyond the scope of this blog post.

Cool, let’s define out request struct now

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct Request {

pub method: Method,

pub path: String,

pub headers: HashMap<String, String>,

pub params: HashMap<String, String>,

pub body: Body,

}

The reason I didn’t use plain String’s for method and body are cuz we’re in rust and can handle it with proper sum types. Let’s do that

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

pub enum Method {

GET,

POST,

PATCH,

PUT,

DELETE,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

pub enum Body {

Json(serde_json::Value),

Bytes(Vec<u8>),

Text(String),

}

The PartialEq macro is so that we can later perform == checks in our tests, for example.

Now, we want to have the method enum as an abstraction to our handlers, but how do we come to that from the plain string bytes in our TCP stream? Here’s how…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

impl FromStr for Method {

type Err = ();

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

match s.to_uppercase().as_str() {

"GET" => Ok(Method::GET),

"POST" => Ok(Method::POST),

"PATCH" => Ok(Method::PATCH),

"PUT" => Ok(Method::PUT),

"DELETE" => Ok(Method::DELETE),

_ => Err(()),

}

}

}

We simply need to implement the FromStr trait, so that simply calling "POST".parse()? will get us our Method enum, that’s the beauty of rust 😁

Okay, now let’s write a new method for our body… to convert from Vec<u8> that we’ll get from TCP.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

impl Body {

pub fn new(buf: Vec<u8>) -> Self {

match serde_json::from_slice(&buf) {

Ok(v) => Body::Json(v),

Err(_) => match String::from_utf8(buf.clone()) {

Ok(s) => Body::Text(s),

Err(_) => Body::Bytes(buf),

},

}

}

}

I’m first having serde try to parse it as json, if that fails, we try a utf-8 conversion. Finally, if both these fail, we use the bytes variant

Cool. Now that we have the building blocks in place, let’s write the actual parser. Our parse function takes in a byte vector and returns a Request object. pub fn parse(buf: Vec<u8>) -> Result<Self> {}.

note: this could’ve been ‘new’, but since there’s no concept of constructors in rust, I chose to use a more meaningful name here

So the key here is that apart from the body, the rest of the request stream is a String, once we get that, we can perform string manipulation to get our request attributes.

Body

We know that the headers and the body are delimitted by \r\n\r\n.

But converting the whole things to a string prematurely and say, spliting would be unwise as it could corrupt our non utf body, not to mention the unnecessary serialization cost

Instead, we create a byte seperator, let sep = b"\r\n\r\n" and use the .windows.position approach to find the index of the seperator like so…

1

2

3

4

if let Some(pos) = buf.windows(sep.len()).position(|window| window == sep) {

let meta = String::from_utf8(buf[..pos].to_vec())?;

let body = Body::new(buf[pos + 4..].to_vec());

}

Once we have the position of the seperator, the payload up to that is our metadata, containing headers and other information, and anything after that is our body.

note: the +4 is to cover for the length of the seperator itself, which is 4 note: this is the most common approach, it is

O(n), but should be okay since the number of headers is usually small. We could look at faster options like using a crate with simd optimizations for string lookup

Let’s now go about extracting the various request attributes from meta

Method

We know that the first line is, e.g. GET / HTTP/1.1.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

let mut parts = meta.splitn(2, "\r\n");

let info = parts.next().ok_or("malformed http payload")?;

let mut info_parts = info.trim().splitn(3, ' ');

let method: Method = info_parts

.next()

.ok_or("missing HTTP method")?

.parse()

.map_err(|_| "invalid HTTP method")?;

the first line is spliting meta into two parts with \r\n as the delimitter. This gives us an iterator, which we can call next() on to get our first line, info. If the split is not possible we error out like shown

Now, we split info_parts into three with ` ` as the delimmiter. The first of which is our method.We then call parse() on it which invokes the FromStr trait implementation we wrote earlier to get our Method enum

Path

The second part of info_parts is going to have our request path

1

2

3

4

let path: String = info_parts.next().ok_or("missing HTTP path")?.to_string();

let url = Url::parse(&format!("http://dummy.host/{}", &path))?;

let path = &url.path().to_string()[1..];

let path = path.to_string();

But it could also include query params, which shouldn’t be included in our request attribute. Thus, we parse the url and get the proper path string

Params

We can use the same parsed url object to get the query params

1

2

3

4

let params: HashMap<String, String> = url

.query_pairs()

.map(|(k, v)| (k.to_string(), v.to_string()))

.collect();

Here, I’m converting the query pairs to String, and then collecting into our HashMap<String, String>. See how readable rust’s functional iterators are compared to having yet another procedural loop…

Headers

Another beautiful aspect of the fact that splitn gives us an iterator instead of say an array, (which is also an iterator in rust, but that’s beside the point) is that when we called .next() earlier to get our info for extracting the first line, it also removes it from the iterator.

So now, if we call parts.next(), we’ll only get the headers. No need to do any messy replace() or remove() calls.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

let headers: HashMap<String, String> = parts

.next()

.unwrap_or(": ")

.to_string()

.split("\r\n")

.filter_map(|s| {

let mut header = s.trim().splitn(2, ": ");

Some((

header.next()?.trim().to_string(),

header.next()?.trim().to_string(),

))

})

.collect();

Since next returns an option, we need to account for it being None as well, that’s what the unwrap_or is for, just initializing it with an empty header.

We then again perform a splitn with \r\n which will give use an iterator of header strings

Using filter_map, we can split with : on each item in this iterator and return a tuple of key value strings, which we then collect into our HashMap<String, String>.

This kind of code may be harder to write, and it indeed takes a while to get a hang of (you can always ask gpt), but once written, it’s so much better for readability. Not to mention the internal optimizations that can be then added to these functions, by using crates that provide similar abstractions, but do crazy stuff like simd optimizations internally.

Here’s the full parser function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

impl Request {

pub fn parse(buf: Vec<u8>) -> Result<Self> {

let sep = b"\r\n\r\n";

let (method, path, headers, params, body) =

if let Some(pos) = buf.windows(sep.len()).position(|window| window == sep) {

let meta = String::from_utf8(buf[..pos].to_vec())?;

let body = Body::new(buf[pos + 4..].to_vec());

let mut parts = meta.splitn(2, "\r\n");

let info = parts.next().ok_or("malformed http payload")?;

let mut info_parts = info.trim().splitn(3, ' ');

let method: Method = info_parts

.next()

.ok_or("missing HTTP method")?

.parse()

.map_err(|_| "invalid HTTP method")?;

let path: String = info_parts.next().ok_or("missing HTTP path")?.to_string();

let url = Url::parse(&format!("http://dummy.host/{}", &path))?;

let path = &url.path().to_string()[1..];

let path = path.to_string();

let params: HashMap<String, String> = url

.query_pairs()

.map(|(k, v)| (k.to_string(), v.to_string()))

.collect();

let headers: HashMap<String, String> = parts

.next()

.unwrap_or(": ")

.to_string()

.split("\r\n")

.filter_map(|s| {

let mut header = s.trim().splitn(2, ": ");

Some((

header.next()?.trim().to_string(),

header.next()?.trim().to_string(),

))

})

.collect();

(method, path, headers, params, body)

} else {

return Err("unterminated request buffer".into());

};

Ok(Self {

method,

path,

headers,

params,

body,

})

}

}

You could ofcourse seperate thise into functions for each parsing, but these days I’m inclining more towards the locality of behavior principle then uncle bob’s clean code, again… a discussion for another day 😁

Response Builder

Let’s define the response struct and an enum for known status codes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

pub struct Response {

pub body: Vec<u8>,

pub headers: HashMap<String, String>,

pub status: StatusCode,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub enum StatusCode {

Ok = 200,

Created = 201,

Accepted = 202,

NoContent = 204,

BadRequest = 400,

Unauthorized = 401,

Forbidden = 403,

NotFound = 404,

InternalServerError = 500,

NotImplemented = 501,

BadGateway = 502,

ServiceUnavailable = 503,

}

impl StatusCode {

pub fn as_http(&self) -> String {

let reason = match self {

StatusCode::Ok => "OK",

StatusCode::Created => "Created",

StatusCode::Accepted => "Accepted",

StatusCode::NoContent => "No Content",

StatusCode::BadRequest => "Bad Request",

StatusCode::Unauthorized => "Unauthorized",

StatusCode::Forbidden => "Forbidden",

StatusCode::NotFound => "Not Found",

StatusCode::InternalServerError => "Internal Server Error",

StatusCode::NotImplemented => "Not Implemented",

StatusCode::BadGateway => "Bad Gateway",

StatusCode::ServiceUnavailable => "Service Unavailable",

};

format!("HTTP/1.1 {} {}\r\n", *self as i32, reason)

}

}

The as_http methods is pretty self-explanatory, it takes in the status code as an integer and interpolates it in the HTTP/1.1 conformant format, forming the first line of our response.

We need an abstraction that accepts byte body and status, and lets use set response headers before returning.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

impl Response {

pub fn new(body: Vec<u8>, status: StatusCode) -> Self {

let mut headers = HashMap::new();

headers.insert("Content-Length".to_string(), format!("{}", body.len()));

Self {

body,

headers,

status,

}

}

pub fn set_header(&mut self, key: &str, val: &str) {

self.headers.insert(key.to_string(), val.to_string());

}

}

The headers hashmap is initiated with a Content-Length header, which is simply the length of the body. The set_header then takes a mutable reference to self, in order to add more response headers.

Now it’s time to cnovert this to an HTTP/1.1 conformant response

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

impl Response {

pub fn to_bytes(&self) -> Vec<u8> {

let mut res: String = self.status.as_http();

for (k, v) in self.headers.iter() {

res += &format!("{}: {}\r\n", &k, &v);

}

res += "\r\n";

let mut res: Vec<u8> = res.into_bytes();

res.extend_from_slice(&self.body);

res

}

}

The as_http call on the status fives us our first line. Then we iterate through our headers and interpolate them in the HTTP/1.1 format.

Note that, so far, our response object was a String. Once we’re done with the headers, we add theanother \r\n to form the \r\n\r\n delimitter between headers and body, and convert it to a byte vector. Then, we simply extend it with our body slice, forming our response as Vec<u8>

We can now use it in our handle_connection function, like so…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pub async fn handle_connection(mut socket: TcpStream, routes: Router<Handler>) -> Result<()> {

let mut buf = vec![0; 1024];

loop {

let n = socket.read(&mut buf).await?;

if n == 0 {

return Ok(());

}

let body = buf[..n].to_vec();

let request = Request::parse(body)?;

let res = handle(request);

socket.write_all(&res).await?

}

}

The handle function looks like this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

pub fn handle(req: Request) -> Result<Response> {

tracing::info!("received req: {:?}", &req);

let res = Response::new(

serde_json::to_vec(&json!({"msg": "success"}))?,

StatusCode::Ok,

);

Ok(res)

}

It’s starting to look like a proper micro-framework now, right? 😄 We should be able to run the server at this point, but there’s one thing missing.

We can’t just go about adding the handler methods directly to our listen function.

Router

That’s where our router comes with. Essentially it’s a map our routes to functions to be called. But instead of using the general purpose HashMap<_, _>, we’re gonna go with the Router map from the matchit crate.

This is the same crate internally used by the likes of Actix/Axum, so doesn’t need much introduction ;)

Let’s update our server struct to include this router

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

use matchit::Router;

pub type Handler = fn(req: Request) -> Result<Response>;

pub struct HTTPServer {

pub addr: String,

pub routes: Router<Handler>,

}

It’s essentially a map of string to a generic T, which we’ve specified as our custom type Handler. This encapsulates our handler type’s expected signature and makes it cleaner as part of function signature, aiding maintenability

Now, let’s add a function that lets us add routes to our server

1

2

3

4

5

6

impl HTTPServer {

pub fn route(&mut self, path: &str, handler: Handler) -> Result<()> {

self.routes.insert(path, handler)?;

Ok(())

}

}

This takes a mutable reference to the server, and insers the given path, and handler to the matchit router map. If the given handler doesn’t meet the required signature, it’ll error out at compile time, similar to axum

We now need a function to query this map, while handling client connections

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

pub async fn route(request: Request, routes: Router<Handler>) -> Result<Vec<u8>> {

tracing::info!("routing to: {}", &request.path);

let res = match routes.at(&request.path) {

Ok(matched) => {

let handler = matched.value;

let response = handler(request)?;

response.to_bytes()

}

Err(_) => {

let mut status = StatusCode::NotFound.as_http().into_bytes();

status.extend_from_slice("Content-Length: 0\r\n\r\n".as_bytes());

status

}

};

Ok(res)

}

If a match is found, we call the handler and return it’s response. If not, we return a 404 Not Found status code with Content-Length set to 0. Let’s now invoke this from handle_connection

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pub async fn handle_connection(mut socket: TcpStream, routes: Router<Handler>) -> Result<()> {

let mut buf = vec![0; 1024];

loop {

let n = socket.read(&mut buf).await?;

if n == 0 {

return Ok(());

}

let body = buf[..n].to_vec();

let request = Request::parse(body)?;

let res = route(request, routes.clone()).await?;

socket.write_all(&res).await?

}

}

Here, we write the response from route to the socket returning it to the client. We can now update our cmd and bask in the “axum-like” glory of our abstractions 🤣

1

2

3

let mut server = HTTPServer::new();

server.route("/api", handle)?;

server.listen().await?;

cURL it up

That’s it, we can now run our server and call our api’s with cURL

Happy HTTPing…😄

Future work

We can always add features like extractors, and middlewares to make it more usable in the real world. Let’s leave that as an exercise, You can find the codebase on github

Wrapping It Up 🚀

And there you have it—HTTP, stripped down to its bare essentials, demystified, and rebuilt from scratch like it’s 1991 all over again. Turns out, it’s just some text, a couple of newlines, and a sprinkle of networking magic. No black box, no sorcery—just a simple protocol doing simple things.

But here’s the real kicker: reinventing the wheel is underrated. You don’t really understand a thing until you’ve built it yourself, and HTTP is the perfect example. Sure, you could just use Axum, Actix, or whatever’s trending on GitHub today, but where’s the fun in that? Breaking things, debugging raw sockets, and seeing your first valid HTTP response—that’s how you level up.

So go ahead, keep re-inventing wheels. Who knows? You might just end up building a jet engine. 🚀